Mississippi 4th graders outperformed the nation

Good news and bad news from The Nation's Report Card

Standards and accountability have become a defining feature of American education in the decades since the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. There are obviously some downsides to the ubiquity of standardized testing, but the upshot is that it has become relatively easy to gauge and compare student achievement between school districts, individuals, and even entire demographic groups.

But because there are no universal nationwide standards (remember Common Core?), there remain two relative blind spots: national progress and state-by-state comparisons.

Our only tool here is the National Assessment of Educational Progress, better known as NAEP or “The Nation’s Report Card.” NAEP only covers a handful of subjects in a handful of grades (primarily 4th and 8th grade math and reading), but every couple of years it provides invaluable insight into the state of American education.

Results for 2024 are out today, and spoiler alert: it is mostly bad news. Nationally, both 4th and 8th grade reading proficiency is declining. The lowest-performing students are falling even further behind their peers, contributing to a growing “achievement gap.”

But there is a bright spot here, and it is in Mississippi.

Mississippi 4th graders shock the nation (again)

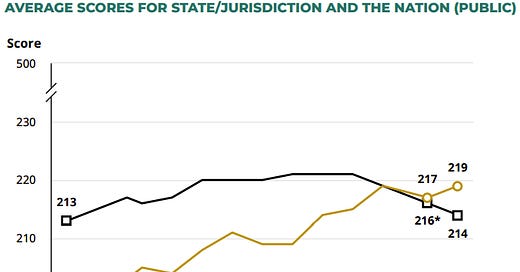

In 2019, Mississippi 4th graders matched the national average on the NAEP reading assessment. This was a historical first and a major coup for public education in Mississippi. It’s also the origin of the term “Mississippi miracle.”

Well, Mississippi 4th graders made history again.

Although 4th grade reading proficiency in Mississippi has remained statistically flat (the average score is higher in 2024 than 2022, but the increase is not “statistically significant”), national scores decreased to an extent that Mississippi 4th graders outperformed the national average on the NAEP reading assessment for the first time ever. That’s a really big deal!

On a state-by-state basis, Mississippi outperformed a total of 20 states (including my native Vermont) and scored in line with a total of 29 states. The only state with a statistically higher score was Massachusetts. (Mississippi was also outperformed by the Department of Defense Education Activity, or DoDEA, which is a federal school system that generally outperforms most states.)

These scores are a major achievement for Mississippi 4th graders and their teachers—and a major wake-up call for much of the United States. Experts credit Mississippi’s embrace of the “science of reading” (best exemplified by the 2013 Literacy-Based Promotion Act—more on this below) as the catalyst in boosting literacy, and I would expect other states to begin paying even closer attention to the Magnolia State.

But what about 8th grade?

In last week’s legislative roundup, I highlighted a bill (House Bill 857) that would expand aspects of the 2013 Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA) from early elementary grades to middle school. It’s worth mentioning again that the LBPA—which provides a series of targeted literacy supports and interventions—only pertains to the years leading up to 4th grade.

Because the LBPA is laser-focused on these early grades, probably one of the best arguments for its effectiveness is that 4th grade reading proficiency has skyrocketed in the past decade—while 8th grade reading proficiency has remained basically flat.

That trend continued this year.

Although the 8th grade reading proficiency gap between Mississippi and the national average has narrowed in recent years, this is largely the result of a decline in the national average. Mississippi 8th graders still trail 27 other states in reading—as opposed to just one state in 4th grade.

This is a great argument for expanding the “Mississippi miracle” to middle school, and my free advice to proponents of HB 857 is to start talking about disparities between 4th and 8th grade reading proficiency (this was not mentioned at all by lawmakers when the House Education Committee voted on HB 857 last week).

Persistent socioeconomic, racial, and gender gaps

I could continue tooting Mississippi’s horn on reading proficiency, or I could dive into math scores (Mississippi 8th graders trail the national average somewhat, while 4th grade proficiency was not statistically different from the national average). But we also need to reckon with the persistent (and substantial) achievement gaps by race, gender, and socioeconomic status.

Here are some of those gaps among Mississippi 4th graders in reading:

Economically disadvantaged students scored, on average, 26 points lower than students who are not economically disadvantaged

Black students scored, on average, 25 points lower than White students

Hispanic students scored, on average, 16 points lower than White students

Male students scored, on average, 8 points lower than female students

We see similar achievement gaps in 8th grade reading, as well as in both 4th grade and 8th grade math (aside from gender gaps). The largest disparity I’ve seen is that 8th grade Black students scored, on average, 29 points lower in math than White students.

What’s interesting (and troubling) is that these achievement gaps have stayed largely the same over time. Compared to results in 1998, none of the racial or socioeconomic achievement gaps are statistically different. There is improvement across the board, but 20th century disparities have remained persistent well into the 21st century.

Without going too much into detail here (this is a subject for a dissertation, not a blog post), a lot of the disparities in student achievement are exacerbated by the vast disparities in resources between public schools in Mississippi.

To highlight a few examples from my own research when I was at Mississippi First:

For much of the 21st century, Mississippi had a school funding formula that often directed more state public education dollars to districts with lower rates of student poverty. Combined with the fact that poorer districts generally have a harder time raising local revenue, this put high-poverty districts at a huge disadvantage in terms of resources. (Thankfully, the state’s new formula, passed in 2024, is designed to do the exact opposite.)

In the 2021-2022 Mississippi Teacher Survey, I found that self-reported attrition risk was statistically higher among teachers in school districts with a “D” or “F” accountability grade, as well as in majority-Black districts. Teachers in these districts were more likely to be planning to leave their classroom (compared to higher-rated districts or majority-White districts), complicating efforts to boost student achievement.

In a 2024 analysis of district accountability data, I found that teacher turnover (not just self-reported attrition risk, but actual turnover) was indeed higher in districts with lower ELA and math proficiency. Relatedly, students in these districts were also less likely to have teachers who were experienced, licensed, and teaching in their field of study.

Basically, if you’re a student in Mississippi and you’re attending a school that is high-poverty, low-performing, and/or majority Black, you are less likely to have access to the resources you need to be successful. Mississippi made progress on the funding aspect of this with the Mississippi Student Funding Formula, which was passed in 2024 and is designed to send additional state dollars to higher-poverty districts. But access to teachers remains remarkably uneven.

There are, of course, plenty of non-school factors that contribute to persistent achievement gaps. But, at the very least, an inequitable distribution of resources (school funding, licensed teachers, etc.) makes it exceedingly difficult to shrink these gaps.

Mississippians should absolutely celebrate our impressive performance in the face of dismal nationwide results. But those achievement gaps aren’t going to go away on their own.